I think we’ve all been guilty at some point or another of looking for signs. In A Very Long Engagement, the main character, Mathilde, frequently tries to create signs that will confirm her belief that her long-lost fiancé is still alive, even though he’s been MIA for the few years following the end of World War I. As she sees more and more signs "confirmed," she feels her conviction grow and her motivation to find her fiancé is heightened. This pursuit very much reflects the ideals of Romanticism because Romanticism focused a lot on our human connection with something more supernatural--something reason and logic couldn't quite explain. Throughout Mathilde's pursuit, she was told numerous times to give up, that her fiancé was gone, that she was going to end up hurting herself, but despite all the reason and logic fighting against her, she held on to belief and hope, her inexplicable certainty that he was alive.

Holding on to those views of transcending reason during a time of war when everything seemed grim and hope was a distant memory for many people would have been challenging, but this just shows how powerful the ideas were of the Romantic Era. It was so important that those ideas preceded WWI because without that connection to something bigger, all hope would have been lost. If the war would have started after the Enlightenment, the logic and facts of the carnage and horror would have been enough to beat away any glimpse of hope.

A Very Long Engagement goes to show that the themes of Romanticism didn't disappear after the war. They were what kept people sane, with or without the happy ending. The feelings of hope and peace that you have even when there is no reason for them to exist are what keep the world moving forward. We should all be grateful to Romanticism for helping us to trust in these supernatural connections that keep us moving forward.

image credit: public domain images via Wikimedia Commons

Saturday, November 10, 2018

We Are All Miners

Going into Comradeship (Kameradschaft in the original German), I didn't know exactly what to expect or how it would connect with World War I. After watching the movie, thankfully with English subtitles, I still wasn't entirely sure what it had to do with WWI. Thank you Wikipedia! After getting a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding the events of the film, I finally understand it's significance to the First World War and to romanticism.

To give you a quick recap of the movie, Comradeship portrays the real-life event of a French mine, with the structural integrity of a Jenga tower, near the border between France and Germany catching fire and a German rescue team comes to save the surviving miners. This all happened not long after WWI, so France and Germany weren't exactly on the best terms with each other. As an example, there is one point where one of the rescue crew members goes to save a miner and the miner, seeing the German facemask, suddenly flashes back to fighting German soldiers in WWI and proceeds to attack the man. Granted, this is due to PTSD, but it's not the only instance of the tension between these two peoples. There is also a group of three German miners that the film focuses on who are shown as not really liking the people of France, so you get to see the discrimination from both sides.

The movie ends with both peoples realizing that they don't need to dislike each other anymore, because they're all miners! In all seriousness, the overarching message of the film is truly that different countries can, and should, live in harmony with each other, deconstructing the idea of nationalism to some extent because they were only able to fix the situation after looking beyond their national identity and pride, their romanticized, individualistic view of themselves, to see that, whether French or German, they're all human and other labels don't matter. This is definitely a message that is still pertinent to our time and should be something we all strive to live by.

Image Credit: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0022017/ Eureka Entertainment

Nationalism, Compassion and a Star-Spangled Tattoo: Wings

Isn't he just the funniest "German" you've ever seen?

Wings is a story, a film, about World War One, in a time before it was known that there would be a "World War Two". During that perilous time of conflict nationalistic ideologies were on the rise as anti-"blank" sentiments heated up, mostly due to the "monstrosities" each side was perpetuating in their propaganda. The American characters, both main and side, use deragatory terms to refer to the German forces, and steal trophies from their destroyed vehicles. It is in the midst of this hatred that the film's comic relief figure, Herman the German (played by El Brendel), is introduced. While not the focus of the film, it is Herman's personality and actions which help to truly show the positive aspects of what it means to be an American. Being of German descent and having a German name, Herman is looked down upon at best and physically assaulted at worst multiple times for being a percieved "spy" when trying to enter the armed forces. It's only when he can reveal his right bicep, which has a tattoo of the stars and stripes on it, that the others are convinced of his patriotism. Throughout the film he is the target of slapstick humor, constantly being punched and shoved, and in one of the film's more serious moments, gets kicked out of the Air Force. Despite all of this, he always gets back up, ready to take more if needed, and after losing his chance to become a pilot becomes a mechanic instead so that he would still be involved in the aviation program. His determination and "never-give-up" attitude help show the reader the core behind the American spirit, along with his willingless to always help others. In the last scene he is featured in, one of the most dark in the film, he discovers the lost good luck charm, a small teddy bear, that one of the protagonists drops before he goes off to fly. Running as if for his life, he only just barely misses the pilot as he flies off, but makes it in time to hand the teddy bear off to the second protagonist of the film, an item that becomes extremely important later on. His compassion and patience with others is easily seen in his interactions with the rest of the cast, and with his inclusion the film moves from a dreary drama of the horrors of war to having a sun beam of hope as the audience feels the beauty behind the American Dream.

Wings is a film that starts bright and cheerful and ends in sorrow, albeit with a spot of hope, and in this review I wanted to do the opposite. To be truthful, there is no character in this film that I would ever more want to be than Herman the German. Where others might look towards the resourceful and playful Jack, or the rich but humble friend David, or for the ladies the deterministic and stereotype subverting Mary, I see Herman as the best source for inspiration in this film. I wish I could have even a smidge of his patience and good nature as I go about my time here on Earth, and I hope that one day I can help another like he helps everyone he meets.

Image Credit: "El Brendel" obtained via Wikimedia Commons

The Anti-Sublime

World War I convinced the Enlightenment thinkers who believed they lived in the best of all possible worlds that, in fact, the world was not all crêpes and crème brûlée. In the war, most of Europe had experienced the horrors that people could inflict upon each other first-hand. One result of this was that people became fascinated with the sublime.

A Very Long Engagement, a film by Jean-Pierre Jeunet, explores the themes of that period in multiple layers. The film follows the story of a young French woman, Mathilde, whose fiancé, Manech, is sent off to fight in World War I. She is told he died in the trenches, basically sentenced to death because he self-mutilated. However, there are strings of uncertainty in the story, so she investigates to find the truth for herself.

| Mathilde solemnly plays her tuba while she waits for Manech to return. |

The Individual

In searching for the truth of her fiancé's death, Mathilde explores the lives of other men who had suffered his same sentence alongside him. She finds the unique truths behind their times in the trenches, as well as the truths of the people they left behind in France. These stories give a very personal perspective on a very large war.

The Sublime

The tragic romance of Mathilde and Manech is the classic type people have loved for centuries. It is terrible, but in a melancholy, heart-aching way that is pleasing to experience at a distance. This film entertains that form of the sublime while pushing against a greater one: war. Machine guns obliterate anyone who goes above the trenches into no-man's land, bombs explode and splatter soldiers' viscera onto their friends' horrified faces, men shoot their fingers off with shotguns in efforts to escape the rot-and-lice-ridden hell of the trenches. This film does not glorify the nobility of dying at war; it depicts death in gory, gut-wrenching detail. I, at least, went away from the film solemn and struck with the horrors of war, not inspired to pick up a rifle.

I'll admit the idea of going to battle has at times sounded to me. It was more in the way of fantasy novels in which people fight on horseback with swords and crossbows. Regardless, with its individual approach and challenge to the sublime elements of war, A Very Long Engagement effectively horrified me against the notion that battle is in any way romantic.

Friday, November 9, 2018

That's Not the Point

There is no glory in war. I know that. I don't know it first hand, of course, but I've been taught over and over throughout the years by study of war after war that there is nothing glorious, nothing to be sought after in man's conflict against man. That said, studying WWI drives that home to me more poignantly than any other conflict. Maybe it's the dull waiting of the stale-mated trenches. Maybe it's the bleakness of no-man's land. Maybe it's the devastation and inescapability of mustard gas. Or something else. I don't know.

No one knew. WWI was a war that came at the end of a line of dominoes. No one knew why anyone was fighting, really. And it dragged on. It got messy. It became big. Broken. Incomprehensible. I can't say that I've studied WWI in depth, but every brush I've had with it through art or film or literature has left me with a longing to understand. It seems to pour out of the souls of everyone who was involved in the conflict, either directly or indirectly. "Why? Why did this happen? Why did we allow this to destroy so many lives?"

"A Very Long Engagement" speaks to that longing for truth. It's a beautiful movie that embraces the Romantic ideal of letting some things be too big to be resolved. The heroine, Mathilde, sets herself on a seemingly impossible journey to find the truth of what happened to her fiance in the war. She follows her heart. She leads with her irrationality, and it leads her to rational discovery upon rational discovery. That was actually one of my favorite parts of the film. At crucial moments, when everything seemed to be suspended in uncertainty, hovering over the void of crushing disappointment, Mathilde would seek the truth in the mundane. She'd say to herself, "If my dog comes in before dinner is ready, then there's still hope." She'd wait. Often, the parameters she'd set for her hope wouldn't be filled. But she'd keep going.

She wanted her fiance to be alive. That was her driving purpose. But it wasn't the point. The point was finding the truth. Mathilde hardly wasted time asking "why". She accepted that "why" was too big. To incomprehensible. "What" was what concerned her, and it was the only thing that mattered. The truth could have been hideous, and often was, it wouldn't matter. She needed to know.

Nothing was really resolved at the end of the film. The war had still ruined the lives of almost everyone depicted. People were dead. Holes were blown in reality. Nobody had any answer for why any of it had happened. But resolution wasn't the point. Mathilde found the truth. One unknowable became known,though it was at the price of uncovering a thousand more unanswerable questions. Nothing was fixed. But that was fine. Fixing things wasn't the point.

Photo Credit

|

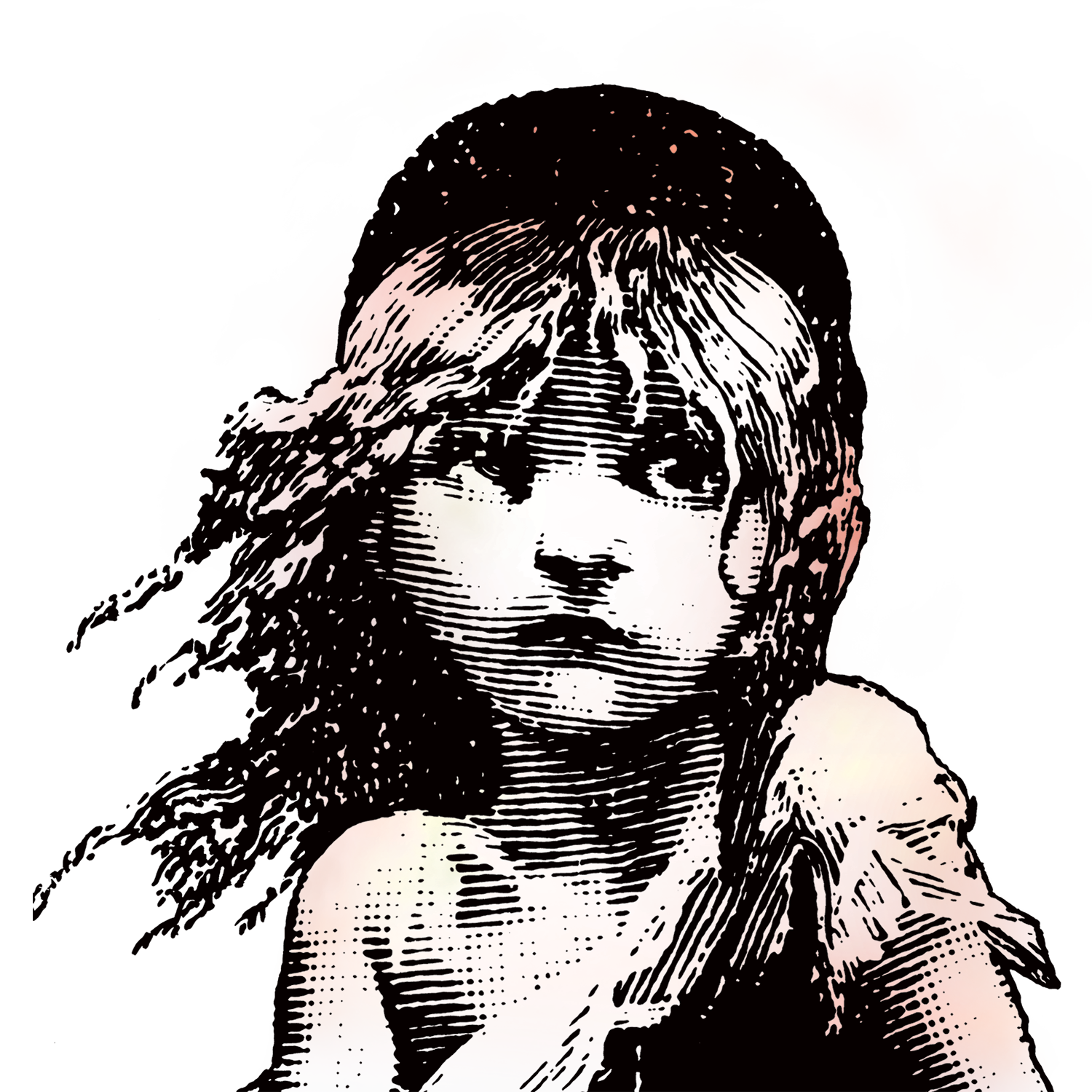

| Art inspired by "In Flanders Feilds" by John McRae |

"A Very Long Engagement" speaks to that longing for truth. It's a beautiful movie that embraces the Romantic ideal of letting some things be too big to be resolved. The heroine, Mathilde, sets herself on a seemingly impossible journey to find the truth of what happened to her fiance in the war. She follows her heart. She leads with her irrationality, and it leads her to rational discovery upon rational discovery. That was actually one of my favorite parts of the film. At crucial moments, when everything seemed to be suspended in uncertainty, hovering over the void of crushing disappointment, Mathilde would seek the truth in the mundane. She'd say to herself, "If my dog comes in before dinner is ready, then there's still hope." She'd wait. Often, the parameters she'd set for her hope wouldn't be filled. But she'd keep going.

She wanted her fiance to be alive. That was her driving purpose. But it wasn't the point. The point was finding the truth. Mathilde hardly wasted time asking "why". She accepted that "why" was too big. To incomprehensible. "What" was what concerned her, and it was the only thing that mattered. The truth could have been hideous, and often was, it wouldn't matter. She needed to know.

Nothing was really resolved at the end of the film. The war had still ruined the lives of almost everyone depicted. People were dead. Holes were blown in reality. Nobody had any answer for why any of it had happened. But resolution wasn't the point. Mathilde found the truth. One unknowable became known,though it was at the price of uncovering a thousand more unanswerable questions. Nothing was fixed. But that was fine. Fixing things wasn't the point.

Photo Credit

Love and War

The first thing I thought when I saw A Very Long Engagement is that Audrey Touruo's role as Mathilde was interesting to see because of another movie I saw her in - He loves me, He loves me not. Without spoiling it I'll just say that this was not the first time she had played a woman driven by love, although the results were very different.

A Very Long Engagement is an examination of World War I at a very personal level, showing the horrors of war, but never concentrating on the war itself. The story revolves Mathilde, who's fiance is sent off to war only to be condemned for self-mutilation. Despite all odds and reason, Mathilde continues to wait for him to return, eventually taking matters into her own hands. One of the ideas that drives the movie is the irrational. Irrationality in continuing to look for a man that is almost guaranteed to be dead, and irrationality of war and how it makes people do strange things. One could say that the movie is framed to show the two sides of man, with his best and worst intentions. Mathilde represents the adaptability of mankind, the ability to be driven to do almost anything no matter the obstacles. Many of the men involved in the "Great War" represent a much baser and fallen nature. One man is shot in cold blood while waving a white flag, just because the sergeant felt like it. Manech (Mathilde's fiance) is condemned to death when he could have been sent home. The commanding officer destroys the pardon letter that could have saved all five condemned men. Why did they do these things? Why was there so much needless killing? These questions are never really answered. Although there have been many movies that show the irrationality of war and the darker side of humanity, what is unique to A Very Long Engagement is how we are shown through Mathilde's eyes the affect of just one day of war and how changing and lasting of an impact it had on so many different people.

|

| Mathilde in front of the Grave of Manech |

There is also a blend of the Gothic in how love and violence are shown, especially in the character of Tina Lombardi. Revenge is a motive everyone can understand, it is something can vindicate even the most monstrous of actions. "Do unto others as they have done unto you" has driven many people and movies. Kill Bill, V for Vendetta, The Princess Bride, Inglorious Bastards, vengeance is an emotion we can all sympathize with. But what is most tragic is how right before Tina is to be executed Mathilde gives her a pocket watch owned by the man she was seeking revenge for. There was a note hidden inside telling her not to destroy herself seeking revenge. The next time we see her, we are shown the only silent black and white scene in the movie, where she is executed via the guillotine.

Nationalism also played a part in the movie, but it really focused on the dividing and painful affects of it, especially in a wartime setting. The guy mentioned earlier who got shot for no reason? The sergeant said right before he killed him "so he's Corsican? Let's cancel his birth certificate." A German woman also helps Mathilde in her search for Manech, sharing a story from one of her relative's point of view. It serves as a very humanizing moment for the Germans as we realize that it wasn't just one side that was suffering, but both. Most didn't want to be there, but had to fight to survive, some did while others weren't so lucky.

A Very Long Engagement's play on words, meaning both a long wait until marriage and a long war serve as the focus of this examination of World War I. War's effects on those fighting and those not on the front lines depict a tragic story, with ripples that spread out to change the lives of hundreds of people. We are shown that behind each soldier is a family, hurt, if not destroyed, by war.

The picture is A Very Long Engagement by Sebastian Japrisot

The Creative Runt of the Family

As the youngest of five children, I grew up seeing my siblings develop and display great artistic talent. It came as no surprise since my dad was an avid painter when he was young. I saw my siblings sing enchanting melodies, draw riveting portraits, and play infectious tunes on a variety of musical instruments. I was quite disappointed the day I realized that my talents in those areas were far from being on the same level as my siblings'. I've since realized that my creativity is channeled in a very different way. I've longed to look at an impressionistic painting and feel a burst of emotion or feel the pull on my heartstrings upon reading a lovely poem, but try as I might, I see art in a very different way. I like art that imitates reality. I like logic. I like raw emotion, exposed meaning. So while I looked through the art of the Romantic Era, I wondered if I would find anything that truly made me stop and feel.

|

| "Fishermen at Sea" Joseph Mallord William Turner |

Joseph Mallord William Turner was from a middle-class family. He didn't have high social standing or abundant wealth. He had his art. He was classified as a prodigy in his youth and continued to receive renown for his artistic genius. What stands out to me though isn't the lines or colors, it's the reality of the scene. It's the fact that I can close my eyes and be in this painting. I can feel the spray of the water and the glimmer of the moon as it reflects off the water. I can look at this painting and feel like I'm a part of it, even without an overly artistic mind. I don't have to study it for an hour with my feet together and my head tilted to one side. I can let the emotions that I already have connect with this scene that feels familiar to me even though I've never been a fisherman at sea.

image credit: public domain images via Wikimedia Commons

Romanticizing the Day of Wrath

Having been a music lover my whole life, I went to my first day of Music 101 my freshman year of college not expecting to learn anything new that semester. Sure enough, much of it was review and the hardest part of the class was remembering which days the tests were open.

By the end of the semester, though, I found I had gotten much more than an A out of the course. It had opened my eyes, or ears I should say, to music from composers and times that I had not before appreciated.

In one unit, we listened to samples of Gregorian chants that were sung in Medieval churches. I was fascinated by the harmonies and stirring melodies, and I wasn't the only one.

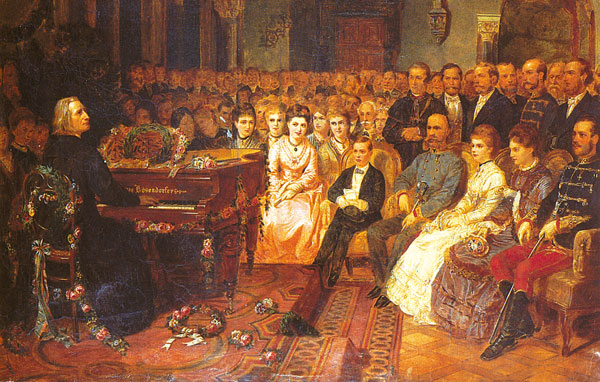

|

| Franz Liszt playing for an audience |

Franz Liszt completed Totentanz: Paraphrase on Dies Irae in 1849. It is a piece for solo piano and orchestra that takes the themes from one of the most haunting melodies from the Gregorian Era and develops it into an amazingly textured creation.

Liszt was a rock star of his time, and romanticizing the slightly grotesque and macabre was the thing to do. In his piece, the simple theme is repeated over and over, swirling across different instruments, octaves, and modes.

This piece has since been on my playlist and I listen to it often. No matter my current emotion, it always seems to satisfy. There are strong booming chords that release any anger in my system. There are fluttering, light moments that feel bouncy and pleasant. There are smooth melodies for contemplative peace and glorious finales for when I am feeling like a conqueror.

Every single listen takes me on that emotional ride and by the time it is finished I feel full and accomplished, and Dies Irae, "The Day of Wrath" is ingrained in my mind.

Image Credit: Wikipedia Commons

I slept the sleep of reason

My freshman year at BYU was one of discovery and enlightenment. I learned about our forefathers in American Heritage. I learned how to write a persuasive essay in writing 150, and how much horse power it would take to push water up a hill at 20 meters/second. However, among all this learning, my favorite class was by far an arts class. We studied art from the baroque master Rembrandt all to way down to Warhol. In the middle, we learned about Goya, and his piece: "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters".

Painting: Francisco Goya, "The sleep of Reason Produces Monsters":

From my first impression, I thought that the artist depicted was troubled by reason. The owls: a sign of intelligence, and them plaguing the artist by night. I imagined that Goya was showing the troubled calling of artists, philosophers and those he thought had reason. At this time, I set up reason as the enemy, the rallying cry of the secular humanists, the shield of atheists and all those who would wish to do the church harm. At this time, my brother was just beginning to research the church from a more secular perspective. I thought he was relying too much on reason, and not enough on the evidence of the goodness of his life, the feelings of his heart. I was worried when he reluctantly submitted mission papers, and distraught when he struggled at the MTC and into the field. I would go to bed every Monday night after emailing him and sleep the sleep of reason. The monsters of doubt and despair would flit through my head, matching the mosquitoes in veracity of attacks. How could he doubt what was clearly so good for me and our family, how can I help if I am thousands of miles away, how can I relieve his suffering?

Now, with an enlarged perspective, I read Goya's caption differently, "the sleep of reason produces Monsters", but as he writes, "Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders." Looking at the painting again, I see that both reason and the artist are asleep. Without reason, we are plagued with the monsters of superstition and dogma. I realized that I need to combine both reason with my imagination and faith in order to produce the "wonders" of a happy life. I have slept the sleep of reason, and let reason sleep, but now I sleep no longer.

Painting: Francisco Goya, "The sleep of Reason Produces Monsters":

- Rights: Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust

- External Link: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

Thursday, November 8, 2018

Escape to the Coast

Albert Bierstadt was a German-born American painter. He was well

known for his landscape paintings of the West. To authentically paint these

scenes, he actually joined others on their journeys to a part of America they

had not yet seen. When Bierstadt brought his paintings back home to the east

coast, people did not believe what they were seeing because they had not seen

nor experienced the landscapes that he had painted.

I chose this painting of the ocean in California because I grew

up in Northern California. If you are from there, and you want to take a drive

out to the ocean, you say that you are “going to the coast.” From my hometown

of Santa Rosa, driving to the coast took about 45 minutes.

My teen years were filled with the divorce of my parents, the

normal drama of girlfriends, and the angst and newness of boyfriends. One of my

favorite things to do was to escape out to the coast, especially very late at

night, never planning which particular road I’d take. There was a tangible

feeling of comfort as my Jensen-Healey sports car and I would wind our way

through landscapes of farms, redwood trees, and small towns. My 8-track tapes

kept me company as they played Cat Stevens and Leo Sayer––I was in heaven. For

several hours, into the dark of the night, I could leave my youthful problems

behind. I owned the night, and it felt good.

Escaping doesn’t last forever, and I eventually had to return and

face my reality, but having somewhere to escape is food for the soul. Just as

the ocean appeared to have no end, when I drove out to the coast, my time alone

there was as an eternity.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albert_Bierstadt_-_Farallon_Islands,_California_(c.1872).jpg

Worlds of Oil: The Mystery of Turner

"It's a Turner."

Identifiable from a good distance away, and pulling me in by a swirl of misty, mesmerizing oil, I found myself standing in front of a Turner yet again-- admiring, loving, embracing the beauty of this painted world. An absolute Turner.

|

| Landscape with Distant River and Bay, Joseph Turner. Musee De Louvre, Paris. |

Joseph Turner was known for his expressive use of light and color in landscapes. Particularly, he loved violent seascapes and inviting countryside scenes. He was raw in his depictions of the elements. Like other Romantic artists (including those in music and literature), Turner was more concerned with feeling than with accuracy. He didn't just paint the wind-- he painted how the wind felt. He didn't just paint sunlight, or the rain, or the turbulent sea-- he painted the warmth of England's rare but beloved sun, the mists of Autumn, and the smack of ocean air against your skin and eyes.

And I suppose that's what gets me about Turner. My mind roams free inside his canvas. The openness of his brushstrokes and generous, dramatic light evoke a mystery and a strange vagueness. And when I look at his paintings, there are no words which come to mind. No critiques, no rambling admiration on technical finesse. Not even a "Wow, that's great." Silence.

Only feelings.

Turner, too, must have craved the silence. As he got older, his fame and demand increasing, Turner became... different. An eccentric. Despite his large sums of money and renown as an artist, he went on long journeys alone. He had no close friends except for his father. He allowed no one to watch him while he painted. He had serious emotional problems with selling his paintings, normally refusing, but feeling completely dejected whenever he did.

Then one day, Turner suddenly disappeared. After months of searching, he was found hiding out in Chelsea, England. He died the day after he was found. And he left all of his living-- 18,000 pounds and change-- for the "decaying artists" of London.

I think it's haunting how well the oil matches its master. Each of Turner's paintings was its own world to get lost in, as Turner demonstrated himself metaphorically. Deep down, I can't imagine his works being created by any other man than one like Turner. When I catch sight of his paintings, I feel isolated myself. My emotions draw me into a familiar yet fantastical world in which I and only I live. And briefly. When I leave the frame's direct view, I'm back into my workaday world and words-- the "tiny little prison" of words-- fill my head and cage me in to the world from which I had been set free by Turner.

Wedding Fanatic

This last spring and summer, I received enough wedding invitations to cover my entire refrigerator. This is not an exaggeration one bit. For two months, every single weekend was booked with wedding receptions. And get this. There were even weekends where I attended multiple receptions, just to make sure that I could congratulate my newly married friends. I’m sure many of you can relate to this, especially those of you who are in my same stage of life. What were your thoughts going to the mailbox day after day and seeing another one “bite the dust?” Now, you might think I am crazy for how I felt about it, but I’m not going to hold back. Each time I opened another invitation, my heart did a little jump.

Meeting Blake's Dragon

When I first learned about William Blake I was in high school, and my education on him was far from complete. I had known him from his poetry for which he was mostly famous, but until I saw a reference to one of his works of watercolor in a movie that I watched a few years ago. After seeing that movie, I did some more research and found more of William Blake's work and was instantly turned on to his style.

Part of the reason that this painting spoke to me is that it came from someone who I thought was known solely for his pieces of literature. Blake being so artistically rounded exemplifies the emphasis on inspiration and aesthetic common in the romantic period.

Blake's work, both in literature and painting focuses extremely on emotion and symbolism, but this painting in particular also focuses on horror and terror to a degree that I would not have thought common for someone such as William Blake. The painting itself is a depiction Blake made for a version of the Bible to include illustrations, and this example is an illustration for the book of Revelations. Revelations, as a whole, is a pretty mysterious and confusing book that is easy to romanticize. The symbolic nature of Revelations bleeds into this painting to create something bizarre, yet intriguing, that is a little bit off-putting for even some today.

This piece of art showed to me that a person does not have to simply stick with one avenue to impress the world, but it stuck out to me because of its dark, eerie style and mysterious stance, showing only the rear of what horrible beast was described in revelations. The piece itself is not logical and does not appeal to any reasonable image that man would see in real life, but it is the basis on the unseen and the emotion, rather than a basis on the seen and factual, that defined romantic art and gave the world masterpieces such as this.

Photo Credit:

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiNrcOG0cbeAhUC2IMKHY7wCK4QjRx6BAgBEAU&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcommons.wikimedia.org%2Fwiki%2FFile%3AReddragon.jpg&psig=AOvVaw2K3PmcSXH-MU5idDiYmtzs&ust=1541829615427911

Musical Time-Travel

I remember at 5 years old sitting at my family's desktop PC in our loft, entranced by the bright green screen as Peter skipped across it to his theme. My Peter and the Wolf computer game wasn't particularly complex or stimulating; it was basically an animated movie set to Prokofiev's music and a narration, but you clicked to move from scene to scene. It was one of my favorites though. Before I started playing music myself, the game—and Prokofiev's composition through it—introduced me to music that could carry you to a different world and completely alter your emotions.

My juvenile computer game served Prokofiev's original goals for his piece well. He was commissioned to write it by the director of the Central Children's Theatre of Moscow in effort to teach children about music and a variety of instruments. The composer himself learned to play the piano out of inspiration from his mother, who played herself, and he wrote his first composition at age 5. He would continue on to write ballets, operas, piano compositions, and more over his lifetime. He began writing music for children after he had some of his own, which is when he wrote his iconic Peter and the Wolf.

Prokofiev's piece is great not only because it is stirring and educational, but also because it tells a story. That's part of why it affected me so much as a kid. I was entranced by the way the instruments, keys, and melodies illustrated the characters and events. The idea has become more common to us now because music is such a core element in movies, but it's amazing how much power of emotion and narrative a piece of music can have.

A few months ago, I listened to Peter and the Wolf again, for the first time in years. I had remembered the game and wondered if I would still enjoy the music—I was not disappointed. If anything, the themes were more stirring than I remembered, and the story even more enchanting. It transported me back to those times I spent in our loft, following Peter and his animal friends on their adventure.

My juvenile computer game served Prokofiev's original goals for his piece well. He was commissioned to write it by the director of the Central Children's Theatre of Moscow in effort to teach children about music and a variety of instruments. The composer himself learned to play the piano out of inspiration from his mother, who played herself, and he wrote his first composition at age 5. He would continue on to write ballets, operas, piano compositions, and more over his lifetime. He began writing music for children after he had some of his own, which is when he wrote his iconic Peter and the Wolf.

A few months ago, I listened to Peter and the Wolf again, for the first time in years. I had remembered the game and wondered if I would still enjoy the music—I was not disappointed. If anything, the themes were more stirring than I remembered, and the story even more enchanting. It transported me back to those times I spent in our loft, following Peter and his animal friends on their adventure.

Desperation

My dad is a graphic artist by trade, so growing up, I learned a lot about art. The art gene missed me. On a good day I can maybe draw a respectable stick figure. But art theory and art history permeated my childhood. I cannot tell you how many hours I spent wandering through museums with my dad, talking to him about different paintings and why they were good. All this to say, I have an interesting relationship with paintings. I feel like I know when one is good, but I could never tell you what it is that makes it that way.

Le Desespere by Gustave Courbet is a painting like that for me. I feel like I know this man. There is something about the expression in the eyes and the gentle tugging of the hair that is striking to me. I can see in this man's face that same kind of blank panic that grips me more often than I like to admit. The warm tone of the painting, and the sharp contrast between light and shadow makes my breath catch- it stills my heart to a stop. When I look at this painting feel like I'm caught in a moment that I've been in a million times. The moment before simmering stress breaks into full panic.

This painting meant a lot to Courbet, too. It was a self portrait, and he carried it with him wherever he went, even into his exile from France. I understand that, on a certain level. As much as desperation and panic are unsavory parts of my life, I have to remember them. Somehow, remembering the times of disorientation makes reality seem more real, and the present more tangible.

Photo Credit

|

| Le Desespere, Gustav Courbet |

Le Desespere by Gustave Courbet is a painting like that for me. I feel like I know this man. There is something about the expression in the eyes and the gentle tugging of the hair that is striking to me. I can see in this man's face that same kind of blank panic that grips me more often than I like to admit. The warm tone of the painting, and the sharp contrast between light and shadow makes my breath catch- it stills my heart to a stop. When I look at this painting feel like I'm caught in a moment that I've been in a million times. The moment before simmering stress breaks into full panic.

This painting meant a lot to Courbet, too. It was a self portrait, and he carried it with him wherever he went, even into his exile from France. I understand that, on a certain level. As much as desperation and panic are unsavory parts of my life, I have to remember them. Somehow, remembering the times of disorientation makes reality seem more real, and the present more tangible.

Photo Credit

An Elegy towards the New World: Dvorak

The Ever-Evolving Composer

The first time that I had ever heard the 4th movement of Dvorak's 9th Symphony was in a video game called Asura's Wrath in 2013. In that game, the rebellious god Asura challenges his old teacher Augus to a battle to the death. As the two deities clash on the lunar surface, the finale to the New World Symphony begins to play as an accompaniment to the clash of fists. Watching this hot-blooded conflict as a high-schooler gave me stars in my eyes, and the song which played stuck around in my head for weeks, and I would find myself humming to it's tune as I walked to class. It was only later, of course, that I would even find out the symphony's name, and could listen to it on YouTube in it's entirety.

Antonin Dvorak (Ahn-toe-nin Di-vor-shack) was the typical musical prodigy common among famous composers having been proficient at the violin since the age of 6. He became famous after his death for mixing African spiritual melodies as well as Native American dances into his most famous work, the 9th or New World Symphony. Considered one of the greatest musical works of all time, a recording of it was brought by Neil Armstrong onto the Apollo 11 mission. Within 30 seconds of the 4th movement's beginning, we have the sort of leitmotif a nefarious warlord would have, as he crushes the world beneath his feet. It transitions into a lighter, but still gray repeating continuation, before descending into quiet, but hopeful stillness with the usage of the flute. Thus proceeds an optimistic march which is interspersed with several brief returns to that oppressing opening. Eventually, we reach the "Largo" of the piece which had been used by Dvorak's student William Fisher for the spiritual song "Goin' Home", which wears it's African influence on it's sleeve. We then transition to long stretches of tranquility before moving into the climax, a true return to the opening once more before the final minutes of victorious trumpets, marking the end of the piece.

Ultimately, the 4th movement tells a story, a story of darkness which conquers all and destroys peace before finally in the end being defeated by a simple good. It's a piece of music which I hold close to my heart.

Image Credit: "Antonin Dvorak" via Wikimedia Commons

The Miserable and the Hopeful

Authors have a gift that for me, transcends that of music or paintings. They depict life as we feel it, a beautiful depiction of the human consciousness hitherto unreached by other mediums. Whoever said a picture was worth a thousand words was wrong, for what we see with our eyes cannot compete with the images we created ourselves in our minds, unfettered by the imaginations of others.

Authors have a gift that for me, transcends that of music or paintings. They depict life as we feel it, a beautiful depiction of the human consciousness hitherto unreached by other mediums. Whoever said a picture was worth a thousand words was wrong, for what we see with our eyes cannot compete with the images we created ourselves in our minds, unfettered by the imaginations of others. Nevermore

Growing up, I had a fascination with Edgar Allen Poe. I was too young to understand his work at the time, and barely read or listened to any of it. I'm not sure why I was fascinated with him, but I was. His name had weight to it, it carried with it mystery, the macabre, and a darkness that should have scared me away, but instead drew me in. Today I think I understand why I was fascinated by Poe. The one story I remember by Edgar Allen Poe is, "The Raven".

This dark poem tells of a man, who in mourning for his deceased love Lenore, finds himself in his chamber late at night. An ominous tapping from outside his chamber startles him, and as he seeks to find its owner he discovers a raven who enters the room. Curious at first, the man questions the raven, seeking to learn the name of his new companion. To his surprise the Raven responds with "Nevermore". Fascination rising, the man continues to question the raven, each inquiry more serious than the last. To each the Raven responds, "Nevermore". By this grim declaration he is told that he will never see again his lost love and that he will never have respite of the pain of losing her. As the poem progresses he descends into madness, tormented by the raven who will leave him, "Nevermore".

Edgar Allen Poe published this poem in 1845, and two short years later his wife died. Two years after that Edgar himself passed away. This poem seemed to foreshadow the remainder of Poe's life. "The Raven" is a masterfully crafted poem which gives us a glimpse of the darkness within each of us and in the world. I feel as though the raven in this story represents our own demons, deep within us, that want us to fail, that want us to grieve and suffer. If we engage our demons at the wrong time or in the wrong way, they can pull us down into the depths of misery and despair. We can break ourselves if we aren't prepared for the darkness inside of each of us. Like the grieving man in the story who curiously engaged with the raven and soon found himself shattered and broken even more than before, each of us deal with our own hardships and losses and we too can engage with our own ravens. But when we do we walk the razors edge between madness and sanity.

The mysteriousness and eerie feeling in this poem connect with me because I have those feelings in myself. I have suffered loss and I have let myself descend into darkness before. I enjoy this type of art not because I like those feelings, but because they are part of me and I need to recognize them and see them for what they are. We all need to stand up to our own ravens and not let them define how our life will go, or how it will end. We need too shoo the ravens within us and give heed to them "Nevermore".

I highly recommend you watch this video in the dark on full screen to get the full effect of this poem.

Deep in Romanticism

Edgar Allen

Poe has many short stories and poems that have always captivated me; this is

going to sound so cliché it may make you sick, but one of my favorite pastimes

is flipping through my collection of Edgar Allen Poe when it’s raining, window

open, maybe sipping on some warm tea from my raccoon mug. Yes, you read that correctly.

The mug in the shape of a raccoon. I think Poe would be proud to know that I

read his works while simultaneously drinking from a cup the shape of a rabid, trash-picking animal.

Edgar Allen

Poe has many short stories and poems that have always captivated me; this is

going to sound so cliché it may make you sick, but one of my favorite pastimes

is flipping through my collection of Edgar Allen Poe when it’s raining, window

open, maybe sipping on some warm tea from my raccoon mug. Yes, you read that correctly.

The mug in the shape of a raccoon. I think Poe would be proud to know that I

read his works while simultaneously drinking from a cup the shape of a rabid, trash-picking animal.

But of all

the works that Poe wrote and of all the poems of his that I have read, there is

one that I have memorized and think of often (I wish I could say

I was cool and can just spout off any Poe poem in any moment but you’ll see the negation

to this below and understand that I am, in actuality, very uncool.)

Deep In Earth, Deep in Romanticism

The poem is

titled “Deep in Earth” and goes like this:

“Deep in earth

my love is lying

And I must

weep alone.”

Pretty

standard cryptic-ness from Poe, right? (And pretty short and therefore, very easy

to memorize. #uncool)

This poem

wasn’t officially written and produced and published like other Poe poems; no,

it was instead found as a slightly faded note on the manuscript for the poem “Eulalie”

which details a happy marriage. “Deep in Earth” as written after Mrs. Poe’s

death and presumably, Poe wrote this as a reaction to this event.

I think

telling an emotional story in less than 13 words is a skill I wish I had and

part of the mysticism of Romanticism.

Embracing Chaos

Personally,

I become too involved with organization and perfection. I love writing, but its

hard to write because the syntax, the rhythm, the meaning, and the reception

must be perfect or I failed. But in all aspects of my life, I find that honesty regarding the chaos of it all brings me closer to understanding, like a personal note of exasperated loneliness, despair and mourning on the manuscript detailing a happy marriage.

must be perfect or I failed. But in all aspects of my life, I find that honesty regarding the chaos of it all brings me closer to understanding, like a personal note of exasperated loneliness, despair and mourning on the manuscript detailing a happy marriage.

Image Credit: Portrait of my Poe collection and Raccoon the Mug

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)