Observation, the long-standing basis of science, seems to be taking a backseat in today's medical community -- a change that is harming patients.

|

| I was misdiagnosed in one of the best hospitals in the country |

I came home from a Christian proselyting mission to the East Coast when I could no longer walk well and had a collection of other severe symptoms.

I thought I was dying.

Before I came home, I was hospitalized in a Johns Hopkins satellite hospital. I was tested for multiple sclerosis, a brain tumor, and Lyme disease. After ruling out multiple sclerosis with the final MRI, the doctor started talking to me as if I were a kindergartner: "Can you come in for bi-weekly visits with a psychiatrist?" I could tell from her tone of voice that she wondered if a nut-job would know the meaning of bi-weekly.

My excruciating physical pain and alarming weakness were incorrectly diagnosed as a psychosomatic disorder (a disease that has no physical cause and results from someone believing fervently that they are sick). After months of debilitating weakness and pain, I got a positive test: it was Lyme Disease. My condition has steadily improved with antibiotic treatment. So how did the best hospital in the nation so glaringly misdiagnose my illness? Most physicians no longer trust their senses to help them make diagnostic and treatment decisions.

The Lost Art of Observation

|

| Hooke's observation of a louse revealed its startling appearance |

In 1665, Robert Hooke stated, "The truth is, the science of nature has been already too long made only a work of the Brain and Fancy: It is now high time that it should return to the plainness and soundness of Observations on material and obvious things." This comment was part of the introduction to his most famous book, Micrographia. Hooke is recognized as the father of modern microscopy. He was among the first to notice the minute details of the world around him, and he recorded his extensive findings in Micrographia.

The idea of using observation rather than preconceived notions as the basis of scientific research emerged during the Enlightenment, a period in history that placed emphasis on using scientific means to discern truth. Francis Bacon, an enlightenment thinker noted for his creation of the scientific method, famously posited, "Man, being the servant and interpreter of Nature, can do and understand so much and so much only as he has observed in fact or in thought of the course of nature. Beyond this he neither knows anything nor can do anything." (Bacon, New Organum, Aphorism 1)

Hooke observed that scientists in his time relied more heavily on philosophical thought and preconceived notions than on actual observation. The sad truth is, my experience of being misdiagnosed through faulty observation is hardly an isolated case. We have reached another point in history where observation is not given enough credence.

Ethos: What We Believe, Why We Believe It

Why do you believe that the sky is blue?

For most of us, this question harks back to our childhood days. Parents often teach their young children colors using whatever is on hand; the sky happens to be the largest blue thing around.

So, when they told you that the sky was blue, why did you believe them?

|

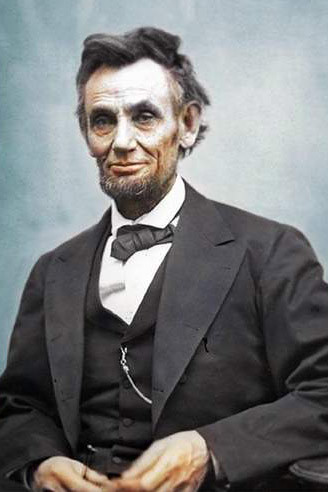

| Lincoln quoted from the Bible to give his plea for national unity more Ethos |

Ethos is a Greek word meaning character. When we say that someone has Ethos, it means they have clout, authority, and power to change people's minds. It means that we want to believe what they say.

Observing the way that Ethos drives our society can provide us with useful insights. Individuals choose whether or not to believe the people and informational sources around them on a minute-to-minute basis each day. Let's take a closer look at qualities that give a source Ethos.

If someone has strong Ethos, they might be:

- an expert on a particular subject

- a person with strong moral character

- someone who can use the words and ideas of well-known, respected individuals to support their point (example: Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address)

So, in other words, you probably believed that the sky was blue because you believed that your parents were experts on the subject of life. Or maybe you believed them because you trusted that they wouldn't lie. Either way, your parents had Ethos.

Humans, We Have a Problem

Today, we are plagued by a sneaky illness: our lack of faith in human senses.

Ethos is inherently part of healthcare in three forms:

- Patient belief in doctors. Without the Ethos that doctors carry as experts in their field, patient demand for treatment by medical professions would not exist.

- Doctor belief in patients. Since patients are the primary observers of their symptoms, they have an expertise on their bodies that cannot be replicated. Listening to patients and tapping into their knowledge about their physical state is a crucial part of diagnostics.

- Doctor belief in their own senses. Doctors must rely on observation through sight, sound, smell, and touch to determine the appropriate diagnosis and treatment for each patient.

Some within the medical community are noticing this lack of observation in modern medicine and are beginning to speak out: "'I sometimes joke that if you come to our hospital missing a finger, no one will believe you until we get a CAT scan, an MRI and an orthopedic consult... We just don't trust our senses.'" (Knox 2010)

As an aspiring medical researcher, I am among the first to get excited about the new technology that can allow for more precise diagnoses. However, I feel that the human element of sensing is slowly seeping out of medicine. I discovered this when the doctors at Johns Hopkins gave more heed to the "healthy" MRI reading than to my pleas for relief from my pain. They did not trust their senses or mine.

It's time to return Ethos to our senses and breathe humanity back into medicine.

We need the gentle intuition of a physician.

Sources:

Second Inaugural Address of Abraham Lincoln

The Fading Art of The Physical Exam, Richard Knox, Article, NPR, 2010

Image credits:

"Luke-warm Hospital Food" by Naomi Sharman

"Micrographia, Robert Hooke" by Smithsonian Libraries is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Photograph of Abraham Lincoln, colorized" by feastoffun.com is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Photograph of a Scientist, Lucas Vasques, made available for public use through Unslpash

No comments:

Post a Comment